- News

- Enabling flexibility in the Rose Hill Solar Saver Trial

The Solar Saver Trial is one of three pieces of work that have been taking place in Rose Hill over the last two years, as part of Project LEO. Project LEO is a large part-government-funded energy trial exploring how we can prosper (financially and in the wider meaning of the word) from the energy revolution that our shift to renewables and commitment to net zero necessitates.

Rose Hill has been one of six place-based trials (‘Smart and Fair Neighbourhood Trials’) sited in six different Oxfordshire communities, exploring the practicalities of an equitable and successful energy transition, through heat pumps, batteries, solar PV and flexibility controls.

About Rose Hill Solar Saver Trial

The Solar Saver Trial concluded last month with a meeting to feed back to participants. It was run by Low Carbon Hub in partnership with Oxford City Council, OX Place, Younity, members of the community from Rose Hill and Iffley Low Carbon, and working closely with Baringa, who have helped us to analyse and interpret our trial data and understand the results.

The trial was open to residents of two sets of new-build flats in Rose Hill, at the Oval and Carole’s Way – the former shared ownership, and the latter, social housing. Both blocks of flats have been built to a high ecological specification and have large sets of solar panels on their roofs.

The aim of the trial was to understand how people living in flats can still benefit from solar panels, even if they do not own them and don’t own the electricity they generate (the panels are owned by Low Carbon Hub and Oxford City Council).

Participants in the trial have been at the forefront of work to explore how they can make best use of the energy generated on the roof, and if they can use energy in a flexible way that has benefits for both them and for the climate.

19 flats signed up to take part in the trial (in exchange for £50 credit on their energy bill, the offer of 6 months of free broadband from Coop Broadband, and the potential for a small financial reward during the trial itself), all in the blocks at the Oval, pictured below:

Changing how we use energy to make best use of the sun

To understand the thinking behind the trial and what we were trying to do, here are some important things to note about how we use and generate energy in the UK:

- Solar panels produce the most energy when the sun shines.

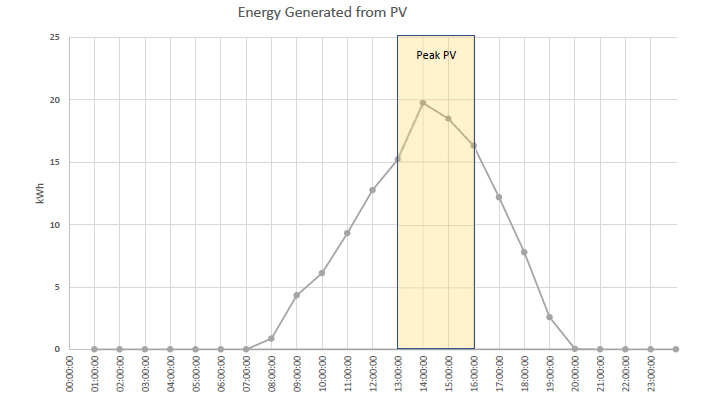

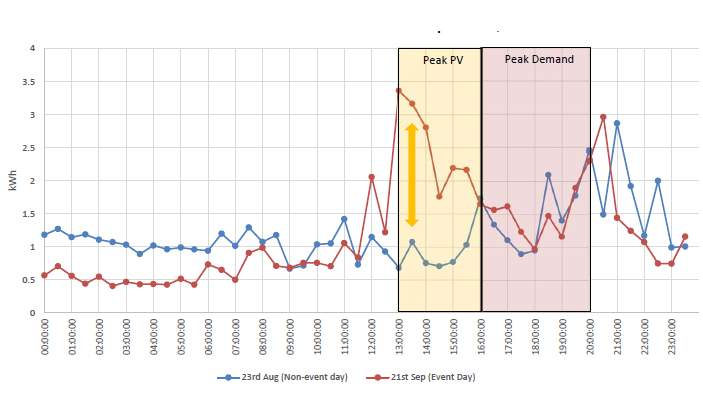

The graph below shows energy generated (in kilowatt hours, kWh) on a typical day by the solar panels on the two blocks of flats at the Oval. Generation peaks (reaches its highest) in the afternoon when the sun shines most directly on the panels, and after analysing the specific generation patterns of the panels on the roof at the Oval, we established they generated the most between 1pm and 4pm. Generation varies with the weather and time of year, but by analysing data from a period of several months, we get a picture of what is likely to happen on average: in this case, a peak between 1-4pm. We call this time ‘Peak PV’.

- People use most energy in the evening.

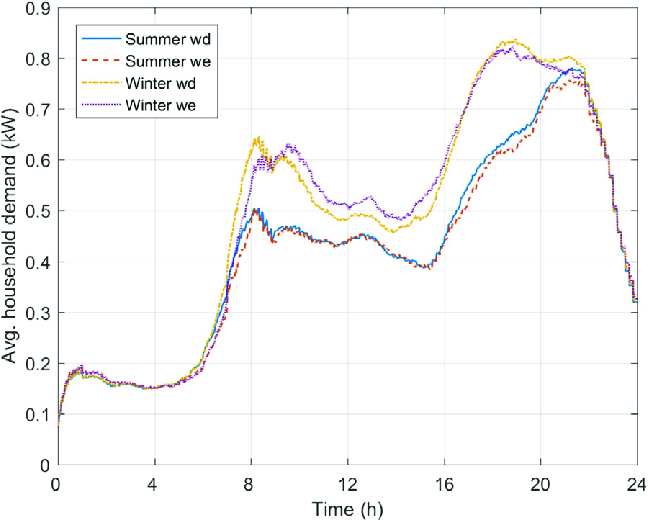

UK households use the most energy, on average, between 4pm and 8pm – i.e. when many people get home from work, cook dinner, put the washing on, etc. The graph shows the average demand for energy in UK households on week days and weekends in summer and winter. Average energy use varies throughout the year, but even in the height of summer, there is still a peak in the late afternoon/early evening.

Demand is at its highest, throughout the year, between 4pm and 8pm, and this time period is called ‘Peak Demand’.

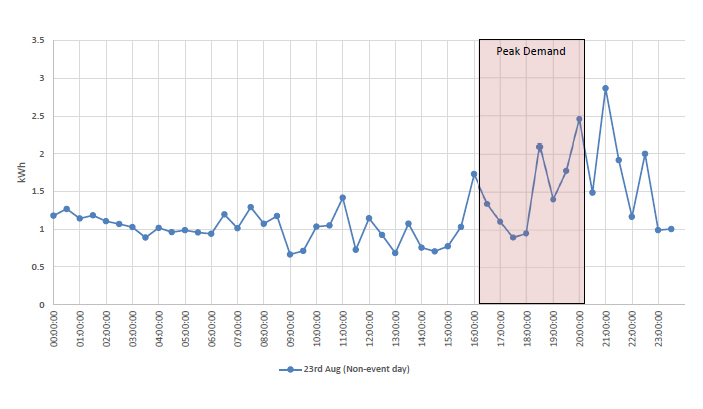

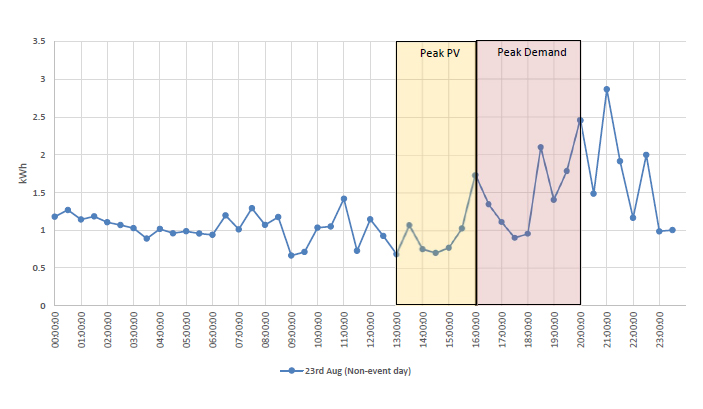

The next graph has been made using real data from the trial and shows the average energy consumption of all the flats participating in the trial on a random non-event day in September. Again, you can see that the graph curve fits the rough pattern of the UK average curve above, with an increase in demand after 4pm.

If we compare the electricity produced by the solar panels to the use of electricity in the flats on a random non-event day, it is clear the Peak PV period does not coincide with when most electricity is used (Peak Demand). In fact, the two windows of time sit side by side.

If we want to make better use of the electricity generated by the solar panels, we need to increase the amount of electricity consumed during Peak PV. In an ideal scenario, we would simultaneously decrease the amount of electricity used during Peak Demand – i.e. shift energy-intensive activities, like running washing machines and using electric cookers, from the evening to the afternoon. What we wanted to understand was whether the residents of the flats could do this when we asked them to.

Why is flexibility important?

There are several reasons increasing flexible energy use and generation is a worthwhile thing to try and do.

The more demand on our energy system, the dirtier the energy production process. We increase the burning of fossil fuels to generate the electricity to meet that need, and therefore produce more carbon emissions in the process. If demand was more stable with less of a peak between 4pm-8pm then less investment in network infrastructure would be required, and more fossil fuel generation could be avoided – we could shut down our dirtiest power stations, some of which exist purely to meet Peak Demand.

What’s more, demand for electricity is going to increase significantly in the next few decades, as we shift towards more electric transport and using electricity for heating instead of gas. The shift is important, but we want to avoid locking ourselves into burning even more fossil fuels to meet the growing demand for electricity. There is a risk, if we don’t start using energy in a clever way, that we will need to generate three times as much as we do already.

Flexibility (i.e., being flexible about when we consume energy) is an important strategy for balancing a future energy system that relies more on renewables, as renewables are harder to dial up and down to meet people’s demand.

Finally, inclusivity and equity: in this trial, we wanted to create the opportunity for residents of the flats to access cheaper, greener electricity, as ideally in our future energy system, you would not need to own the panels to be able to benefit from them being on your building.

What we asked our trial participants to do

Residents were asked to use Octopus as their energy supplier to participate, and to grant us permission to access their smart meter data, which is collected by Octopus on a half-hourly basis. We began collecting energy use data as soon as residents moved in and signed up (most around October 2021), so we could start to get an idea of how the participating flats use energy on a day-to-day basis (i.e., to create a baseline for our trial). In August and September 2022, we then scheduled 13 ‘event’ days. On these days, we asked participants to use more energy between 1pm and 4pm, during Peak PV. The intended scenario was that residents would move some of their more energy-hungry activities away from Peak Demand times in the evening, to do these activities during Peak PV in the afternoon. Residents kept a dairy of each event day, enabling us to gain some insight into what they got up to, what they were able to change, what they found easy, and what got in the way of them shifting energy use.

In addition to the one-off £50 credit on their energy bill and the offer of 6 months of free broadband, each household was offered 10p off every kWh used during the Peak PV slot on event days, and £1 per diary day submitted.

Who took part?

19 flats signed up to the trial, and though we faced significant issues with faulty smart meters which delayed data collection, we were able to get some interesting results.

Results snapshot

If we compare the average flat energy consumption on one of our event days to a non-event day, as shown in the graph below, we can see evidence of increased usage during the Peak PV slot.

Ideally, for this to be a shift, meaning residents moved electricity use from Peak Demand to Peak PV, rather than simply using more during Peak PV and still using the same during the evening (an overall increase in the flats’ energy consumption, and not the best-case scenario), the red line would also be down below the blue between 4 and 8pm, which it is not, in this example. However, what we can see is clear increase during Peak PV, as highlighted by the yellow arrow, which is still something we wanted to show was possible during the trial.

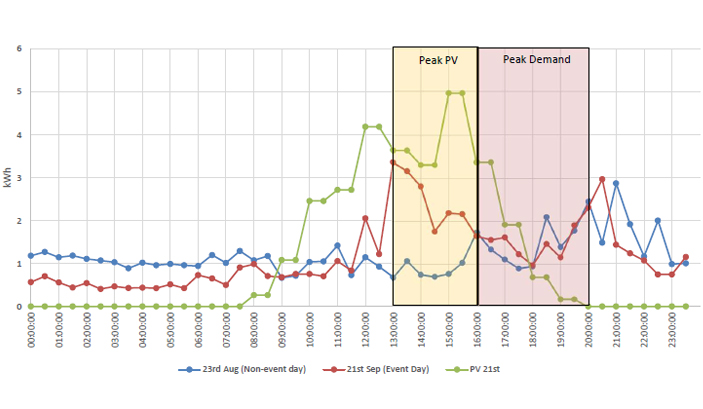

If we then overlay the electricity generation of the solar panels on that day (the green line on the graph below), we can see two things:

- Participants made better use of the energy generated by the panels on the event day (i.e. they use more when the panels are generating).

- There is still more energy being generated that could be used at that time; the space above the red line and below the green is all electricity which is being generated but not being consumed onsite and is instead being exported to the grid.

Flat-by-flat results

In addition to getting a picture of average energy usage in the participating flats, we were able to look at energy use on a flat-by-flat basis and compare the smart meter data to the activity diaries sent in by participants. This enabled us to gain insight into the impact on energy use of specific activities (e.g. using the washing machine), and how easy residents found it to participate.

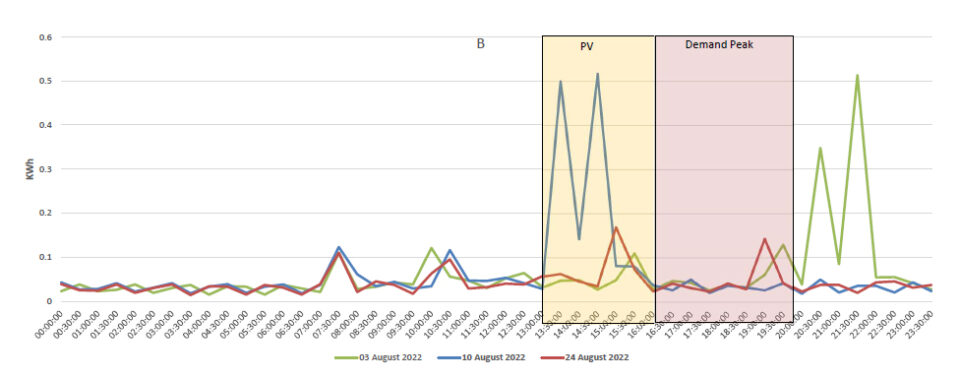

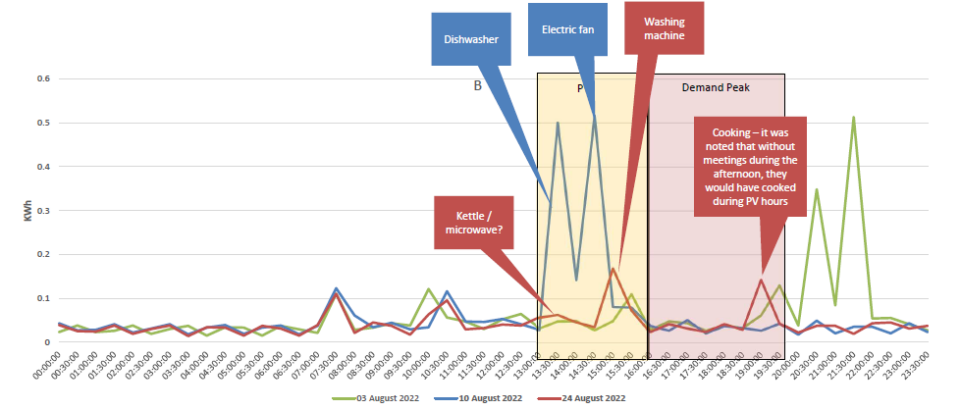

This graph shows the energy use in one flat during the trial. The 3rd of August is a non-event day, and both the 10th and 24th are event days. On the 10th, you can see a perfect shift from using electricity in the evening to using it during the Peak PV period, as requested. The participant found it harder to demonstrate the same flexibility on the 24th of August.

Thanks to the diaries from the event days, we are able to see what activities had an impact, and how work priorities were a barrier to full participation on the 24th.

Community Engagement

It was great to be able to feed back to participants with Baringa’s analysis – each household received a summary of trial results, and details of their own personal contribution, with an invitation to discuss further with us if they had any questions. We presented the results of the trial at a face-to-face event at Rose Hill Community centre in January; those who attended had some great questions and showed a high level of engagement, including expressing a wish to continue to engage and participate in future trials.

Summary of learnings

The trial provided us with a rich set of data. The sample size is small, meaning it is not possible to draw statistically significant conclusions and extrapolate – however, the good news is that it does suggest that the flexibility we were looking for participants to demonstrate is possible – i.e. residents could shift their energy use in a way that makes better use of the electricity generated onsite by the rooftop solar panels.

In terms of incentive payments, we offered 10p/kWh during the 1pm-4pm trial slot, plus £1 per diary entry. 15 flats earned an average of £0.98 for the 13 event days, not including diary payments. This may not seem like much, but if it were continued for a whole year, it would start to add up, with an average of £27.40, and the highest earner in the trial receiving £52.78 per year. We imagine that this is just the tip of the iceberg, with potential for more effective engagement and therefore financial savings, especially as the understanding of flexibility increases. This trial began in October 2021, when there was little public awareness of flexibility in the UK and would probably be quite different following the well-publicised flexibility trials being run by big energy companies in 2022.

In terms of activities which enabled a shift, the most effective were using the dishwasher, washing machine and electric cooker during Peak PV.

Working patterns impacted on people’s ability to participate. For those working from home or doing shift work which meant they were in the home during the Peak PV period, it was easier to participate.

What were the other challenges we faced in the trial?

Covid-19 significantly impacted our ability to engage with residents and trial participants face-to-face. In addition, issues with the smart meters in the new flats led to problems with data collection and access. It is also important that further work is done to try and understand the difference in take up between the two blocks of flats – why did only one social housing tenant sign up, versus 19 in the shared ownership flats?

Overall, this has been a thought-provoking and despite its challenges, successful trial. The results have provided learning that will contribute to the development of an energy system that is inclusive and well-understood and provides opportunities to enable a smart and fair energy system for the future.

By Mim Saxl, Project Manager for Rose Hill Smart and Fair Neighbourhood Trial, Low Carbon Hub.

Publication date;

6th March 2023